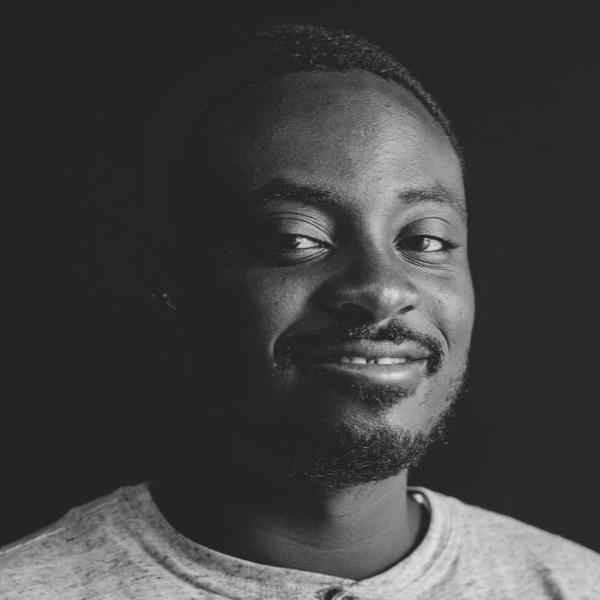

Growing up in the low-income borough of Pointe-Aux-Trembles in Montreal East, Ernest knew firsthand how much a comprehensive approach was needed to address the problems faced by youth in concentrated poverty. From the early days of LBI, he was convinced that youth had a key role to play in solving the challenges they faced as opposed to perpetually living in a system that relied on charitable giving and short-term public solutions. To get there, Ernest also knew that a mindset shift was necessary from community members. By raising expectations and building trust through LBI’s community pact, Ernest utilizes high-quality free sports programs as a means of encouraging young people to first gain knowledge about, then take part in, and eventually lead initiatives that promote community well-being. To develop self-efficacy, Ernest’s long-term approach puts personal transformation as the foundation for social commitment and creative engagement (changemaking).

To respond to the requests of his cousin and other kids from his neighbourhood to learn basketball during the summer break, Ernest started the LBI summer camp program in 2013. From the name and the branding of the organization to fund-raising campaigns to fund the program, LBI began and continues to operate under a youth-led approach and youth decision-making. By signing a contract with LBI and their parents, youth aged 11 to 19 pledge to participate in training lessons starting at 6 a.m. every weekday of the summer. Because LBI places a high level of trust in the capacity of young people at the centre of their programming, this agreement was, and continues to be, the initial bond between beneficiaries and the organization to set high standards in an environment in which it is lacking. In exchange for sports programs in the morning, the LBI camps offer community engagement opportunities in the afternoon such as community clean-ups, gardening, cultural trips, and development workshops. Their development workshops are specifically designed to improve competencies in navigating physical and mental health, promoting healthy lifestyles and habits, establishing personal discipline, and understanding how to engage with community programs.

While programs are offered for free to low-income neighbourhoods, setting high expectations becomes a collective value to foster commitment on the part of everyone involved (youth, parents, LBI staff and coaches). From there, social commitment is practised through recurring volunteering activities and community projects led by LBI or local partners. For instance, in partnership with DéfPhys Sans Limite, a non-profit organization that promotes social inclusion for people with disabilities, LBI youth participate in outdoor social activities, act as companions to support DéfPhys Sans Limite’s members, and contribute to their fund-raising campaigns to sustain the organization. LBI has established local partnerships like these with elementary schools, high schools, community centres, low-income housing programs, and community organizations across their program locations. Through these partnerships, Ernest is also ensuring that projects and activities are delivered with quality in mind. This symbology is critical at LBI because it is how they change youth perceptions of themselves from charity cases to contributing members of society. Because LBI frequently partners with local actors, the symbology has influenced community organization and schools to change their method of operations to design quality programs that truly reflect the needs of their beneficiaries. An example of this is how some high schools consulted LBI on how they can better attract and retain low-income youth participating in after-school activities. This resulted in the schools investing more money in quality equipment and changing their payment methods to allow parents to pay a small amount at the beginning of each session to incrementally cover the total cost of their children’s registration as the year goes on.

Finally, creative engagement (changemaking) is the last step in Ernest’s transformation philosophy which represents an incarnation of his experience: “a regular kid from the community who sought out to bring positive change.” With a newly acquired sense of purpose and with adequate know-how, LBI youth are able to co-create and lead projects and endeavours they deem best to address local challenges. For instance, two LBI alumni started a non-profit organization called My Mental Health Matters, to raise awareness about mental health for young people from diverse cultures and act as a resource hub for racialized youth seeking culturally relevant psychosocial services. Another youth currently involved at LBI recently started an initiative offering hygiene and care kits that contain essential relief items for people who experience homelessness in her community.

Ernest’s community pact has also had great impacts on parents whose children are involved at LBI. Even though it is free, parents are met with quality engagement as if they were paying customers. By continuously listening to parents’ needs and feedback, Ernest and his team have adapted their communication practices to parents’ realities. Since many low-income and immigrant parents work blue-collar jobs, very few use email. As a result, LBI communicates strictly via instant messaging systems or apps such as SMS and WhatsApp to share progress and documentation. To accommodate their schedules, LBI hold parent meetings outside of periods filled with work and household commitments such as Sunday afternoons. With heightened involvement, parents feel a greater sense of community and actively support LBI during local events, community potlucks, and with donations. In the areas where LBI is located, general citizens’ perceptions have shifted towards a better community spirit because young people are now seen engaged in the daytime in parks as opposed to nighttime. Thanks to LBI, residents feel a better sense of belonging and connectedness, which are characteristics lacking under the status quo for low-income boroughs. The long-term and enduring investment in each youth has led many of them to start and lead acclaimed community projects, set up online stores to sell their crafts, and even establish storefront businesses. One LBI alumni became a successful barber and opened the second location of his successful business in the neighbourhood of Pointe-Aux-Trembles where he originally benefited from Ernest’s programs as a teenager in the early days of the organization.

Since LBI coaches spend a lot of time with youth and get to know them personally, Ernest has set up partnerships to ensure that coaches are trained in mental wellness and can foster a safe environment within programs. These partnerships are with key industry experts such as Bell Let’s Talk, Canada’s largest corporate commitment to mental health, and Pour3Points, an organization that enables coaches to become life coaches. This is how Ernest delivers excellence in the accompaniment of youth’s transformation; by ensuring that adults are not only trained to deliver physical sessions, but have the necessary skillset to conduct first aid, offer psychosocial support, serve as a sounding board, and respond in cases of abuse, harassment, and violence. Coaches are an integral part of the community pact, and they represent the organization during frequent engagement and follow up with parents. To make sure that the community pact also benefits coaches and that they show up motivated, LBI is remunerating them with an adequate wage. In comparison with high school coaches, LBI has recently surpassed market standards regarding compensation. As a positive feedback loop, university students who benefited from LBI programs often come back as staff members and seasonal coaches knowing that they will not just receive proper economic opportunities, but they will develop leadership and organizational skills that they can apply in their future employment.

Given that coaches of organized sports in secondary and post-secondary institutions are hired based on their reputation and record of success, a lack of oversight from school officials has led to many cases of abuse and sexual assault in the Quebec sporting community in recent years. In 2022, Ernest spearheaded a coalition of community organizations involved in consultations with the Education and Sports Ministry of Quebec to establish an ethical review committee on coaches and yearly assessment process to make sure that youth can learn and develop while being free from oppression. These consultations continue to evolve and LBI’s practices have become examples of excellence in the delivery of safe and quality programs for youth. If successful, these consultations have the potential to change the culture of athletic programs across the province by introducing the proper checks and balances.

A key part of Ernest’s system change strategy is to make sure that governing boards of learning institutions and organizations that serve youth represent the diversity of background of the kids they are supposed to serve. He empowers parents and youth to seek influential power by becoming board members. Being part of decision-making authorities mean that individuals can better advocate for policies and services that impact their communities. To set an example, Ernest became a board member at the Forum jeunesse de l’île de Montréal (Montreal Island Youth Forum) in 2017. This forum is a consultative body representing over 300 youth groups and organizations in the region that seeks to promote the interests of young people via regional and municipal decision-making bodies. Currently, in a high school in Pointe-Aux-Trembles, nearly half of board members are either youth or parents that have had direct connection with LBI. Along with his staff, LBI alumni, and ecosystem allies, Ernest leverages his position to advocate for change in philanthropic programs, for quality infrastructure, and to share how the LBI philosophy is a viable option to rethink community development initiatives for low-income neighbourhoods.

With a great deal of community buy-in and continuous feedback loops rechannelled into LBI, Ernest started the LBI teams’ program which operates during the school year thanks to successful partnerships with schools. These school partnerships leverage existing infrastructure and resources during the winter months such as indoor courts, equipment, and transportation to and from games/activities for kids whose parents cannot afford private programs. Since its official inception as a non-profit organization in 2014, LBI has reached over 4000 youth and their parents through its scaling deep strategy and long-term approach. Now established in poverty-stricken neighbourhoods in Montreal, Quebec City, and Gatineau, Ernest is looking to expand geographically and deepen his impact in existing LBI locations. Thanks to government grants, private financial partnerships, and peer-to-peer fund-raising campaigns, Ernest’s budget for FY2023 has tripled from the previous year. To ensure that programs are sustainable, Ernest understands that newly established and future locations must be led by proximate leaders who can carry out community change in neighbourhoods they are deeply familiar with. This is why he will soon be launching the LBI Ambassador program to equip young people with the necessary tools, resources, and organizational infrastructure to replicate the LBI model in their areas.

Read less