Introduction

While cultural participation is a human right, society has failed to make it widely accessible. Understanding that inclusion is broadly perceived as complicated and costly to achieve, Lisette sets out to change the practice of key stakeholders in the cultural sector, build an inclusive network with them and leverages that through changing funding frameworks in the political system.

The New Idea

Recognizing that access to cultural life is both a human right and social responsibility, Lisette is enabling cultural stakeholders and institutions in Europe to successfully change their frameworks and practices around inclusion, and thereby working towards the positive participation of people with different abilities in, not only the arts, but also society itself. Over the last 6 years, Lisette has built her organization, Un-Label, as a genuine experimental lab dedicated to shift the social and cultural understanding of what inclusion entails, while creating the infrastructure to help all actors in the cultural sector and beyond to become more inclusive for people with disabilities.

With Un-Label, Lisette is one of the first to develop practical methods for implementing accessibility and inclusivity in cultural landscapes throughout Europe by showing inclusion for what it ultimately is – an easy, natural process that everyone can engage in. In doing so, she uses the cultural sector as an influential lever to shape wider social attitudes and perception towards disability. She provides a platform through which cultural actors with and without disabilities can learn from each other and collaboratively develop initiatives, networks and projects that then serve as exemplary best-practices to show what is possible. Through this, she helps them overcoming fear, stigma and concerns over the difficulty of disability inclusion and act as ambassadors for their new knowledge. Lisette found a unique way to change the system from within by implementing these models under the roof of big cultural institutions like national operas or state theaters with significant reach and influence in the sector and society. Through growing a network of diverse stakeholders from the field, she is bundling expertise and collective power to set new standards across the sector and beyond.

Understanding that changing cultural and attitudinal barriers to inclusion is not enough, Lisette also works on building new funding structures for implementation and the sustainable increase of such inclusive practices. She was successfully involved in the pioneering work for a new financing framework for the city of Cologne in Germany, which now serves as a lighthouse project for other cities as well as for other sectors that are confronted with similar structural barriers to inclusion in Germany and beyond.

The Problem

Culture plays a central role in promoting full human development and realizing human rights. Access to, and participation in, cultural life is mentioned in several international instruments. Participation in cultural life was formulated for the first time in Article 27 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and has since then been reiterated in various forms all over the world. While the cultural sector is known to play an important contribution to economic growth, it has also manifested itself as an important element of social and economic transformation, social cohesion and education for civic democratic participation. We are dealing with key questions of democracy, when asking about cultural participation: Who participates in whose culture? How can we best make diverse cultural voices heard? How can our participation in culture be secured, and who should defend it?

When people are excluded from cultural life, this can have consequences for the well-being and even sustainability of the social order. Participation in cultural life, art and culture is closely linked to citizens’ ability to value diverse perspectives; understand and relate to aspects of life with which they were not previously familiar and to empathizes with others. Empirical evidence supports these claims: Among adults, arts participation is related to behaviors that contribute to the health of civil society, such as increased civic engagement, greater social tolerance, and reductions in other-regarding behavior.

Yet, in practice, not everyone has a chance the experience culture, participate in it or create it. Many people and entire groups in society face significant barriers to their participation (i.e. as audiences, artists and workforce). This affects particularly those that are already at high risk of social exclusion, including people with disabilities, but also racial and ethnic minorities, low-socio economic groups, elderly people, and migrants, amongst others.

According to the Federal Statistical Office, there are approximately 7.9 million people with a limiting long-term illness, impairment or disability in Germany. This group is severely restricted from active participation in the arts, cultural activities and social life in general. Where there are faculties that believe in inclusion, often a lack of know how or technical expertise prevents any changes from happening.

This is despite the fact that cultural and creative industries are in a strategic position to stimulate new thinking, spread openness and tolerance vis-a-vis cultural diversity, and thus act as catalysts for social innovation for the rest of the society and economy. The importance of the cultural and creative sector becomes even more apparent when looking at its economic value added. In 2018, the turnover of the cultural and creative sector in Germany amounted to €168.3 billion. In terms of value added to the German economy as a whole, it represented 3% of Germany’s GDP. This means it outstrips other key economic sectors like the chemical industry, energy suppliers and financial services. Moreover, a minimum of 1.7 million people work in the cultural and creative sector alone, which employs more core workers than any comparable sector; machinery and equipment manufacturing and vehicle construction (automotive industry and other vehicle construction) came closest to it.

However, the proportion of people with disabilities able to benefit from the public expenditure on cultural activities is marginal. The sector has created unconscious structures that are the source of structural, cultural, economic and attitudinal barriers severely restricting their full participation. Besides the physical barriers that disabled audience members face in accessing arts and cultural events, they also face social exclusion in the labor market. In Germany, university of arts are exclusively accessible to people without disabilities, resulting in a very limited existence of a professionally trained artists with disabilities. The broad perception of diversity and inclusion as an element of decreasing quality and professionalism leads to an under-representation of disabled people in theatre, film, and television, both in terms of employment and portrayal. Disabled characters are often played by abled-bodied actors, which continues to perpetuate the myths and stereotypes of the disabled experience.

As a result, the status quo of discrimination and widespread ignorance, fears and prejudices of disability is reinforced, with little or no promotion of the benefits of inclusion. In part, this is also due to the structure and institutional architecture of the German public funding system for promoting and supporting cultural activities. Rather than providing explicit budgets for inclusion, the topic is sidelined into a separate ministerial budget, making it complicated and costly to apply for. Unless the government offers inclusive project financing incentives to all stakeholders in the sector, it will continue to be viewed as low priority, a nice-to-have rather than a need-to-have.

The Strategy

Lisette is building the field for cultural participation of disabled people in Germany and Europe in order to guarantee their equal right towards cultural access, and ultimately make society more inclusive and diverse. With her organization Un-Label, she shows not only that inclusion and accessibility are attainable and feasible goals to achieve everywhere, but also disrupts certain taken-for-granted elements of society, such as the view of disability as a personal deficit or shortcoming. Through creating new opportunities for encounters that would not otherwise occur, she uses the cultural industry as a powerful lever for changing public perceptions and shifting established norms and standards related to inclusion of people with disabilities in society.

Her work is based on three strategic pillars that together feed into her approach to tackle both attitudinal and structural barriers inhibiting the full and equal inclusion of persons with disabilities in social life: She (1) strategically implements high level, high leverage, best practices which demonstrate what is possible (2) connects involved artists and cultural actors to a powerful network of first movers who become multipliers in the sector and (3) works on this basis with political stakeholders to reshape frameworks for funding and incentives.

First, in order to implement high level best practices, Lisette has created Un-Label, a mixed-abled performing arts organization, that paves new ways of creative cooperation between artists from various disciplines and abilities and stakeholders from the field of culture, science and politics across Europe. In the form of productions, workshops, international symposia and artist residencies, Un-Label offers experimental spaces in which cultural institutions and artists with and without disabilities learn how inclusion works by collectively designing, developing and implementing new concepts of high-quality arts productions. These dance and theater productions are presented as national and international guest performances at renowned festivals or within cultural institutions all over Europe. Through these productions, Lisette proves to all sceptics that the combination of inclusion and real art is possible and creates best practices and proof-of-concepts intended to motivate other actors to replicate the approaches. For this purpose, the experiences of participating in mixed-abled productions are being documented and evaluated scientifically by partner universities, from which Un-Label develops open source practical toolkits and guidelines for inclusive project planning. Moreover, the international and diverse composition of the project groups ensures that all participants bring the newly acquired expertise and mindset on inclusion back into their cultural institutions, thereby act as multipliers within the sector.

All projects are aimed to enter the “mainstream” and reach broader audiences through touring and new distribution. As an example, in partnership with the Rhineland Regional Council in Germany Lisette designed and implemented an inclusive roadshow showcasing mixed-abled productions in mainstream venues, such as big city fairs, concerts and rock festivals in the region. This project was particularly successful at opening up new opportunities for encounters, giving people an unexpected art experience in familiar public places. Such public audience encounters help challenge stigma surrounding disability and draws attention to the creative contributions that diversity can make to society. At the same time, the collaboration with the Rhineland Regional Council throughout the implementation process played a key role in enhancing the council's capacity to improve access and inclusion in public places.

Building on the practical knowledge gained through the inclusive productions of Un-Label, Lisette supports and accompanies other cultural actors as well as political stakeholders on their learning journeys to diversity and inclusion. She found a smart way to directly infiltrate the cultural stakeholders in the field without them having necessarily been sensitized to the topic of inclusion. By bringing the mixed-abled productions directly into the key cultural institutions like main opera and theater houses and accompanying the implementation of the inclusion projects from start to completion under their premise, she offers them a low-threshold and relatively easy to implement opportunity to open up to inclusion. This has led to official statements with regard to inclusion from national cultural key institutions. Through creating and uplifting these inclusive role models, Lisette fosters the establishment and expansion of new standards for institutional practices.

Another good example of how her strategy translates into practice is the "Access Maker" project is starting to be implemented in Germany next year. (1) In laboratories, experts from the field come together to collect best-practices and co-create practical guidelines on creating inclusion and accessibility in all aspects of the cultural sector. This information is disseminated through e.g. documentaries and shared with cultural stakeholders, (2) over three years, Lisette accompanies three exemplified theater houses in North Rhine-Westphalia in their opening and transformation into holistically diverse and inclusive institutions and (3) these institutions are integrated directly into a wider network of experts, political stakeholders and cultural institutions where they share their experiences and collectively identify ways for spreading these tested innovations and practical examples to other institutions and sectors. Lisette’s key strength lies in building this collective impact network for boosting efforts and real actionable solutions through sector collaboration, nationally and internationally.

On an institutional level, Lisette works with political actors and public funding decisionmakers at a local, regional and European level to change and adapt the current funding structure whose current set-up disincentivize the cultural sector to implement inclusive measures. Being directly connected to the policy-making field allows her to progressively change the logic and rules of requirements for public funding. As a delegate of the committee of the cultural department of the city of Cologne, she is an active partner in the conceptualization of a new funding framework that will serve as a lighthouse project for other cities in Germany and potentially Europe. This has, for instance, served as a basis for the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia to implement an inclusion commitment clause and a State Action Plan on “Culture and Inclusion”. Over the past 3 years, she has successfully co-designed the set-up of a new department for Diversity and Urban Planning in the city of Cologne, whose tasks include to ensure that other departments prioritize inclusion funding. Given the rigidity of state financial transfers and subsidies for the cultural sector in general and long-time low prioritization of inclusionary measures within this sector, this is a huge milestone in her work. On a European level, she advocates for changes in the EU Cultural Policy by drafting, for instance, a reformed disability inclusion strategy for the Europe Cultural Programs.

Through the above, Lisette works towards changing perceptions and expectations towards people with disabilities held by public and private institutions, people with disabilities themselves as well as their families and friends, and society at large. So far, she has been able to reach over 10,000 people who have played different roles, such as cultural entrepreneurs, politicians, local governance bodies and members of the public. The public arts and cultural institutions serve as a pivotal starting point for this because of its potential to encourage new forms of discussion, spread new ideas and initiate new trends. In the long run, Lisette wants to set a new norm for the whole society where disability is understood as a fundamental facet of diversity, and this diversity is lived as a source of enrichment of all spheres of life. Eventually this can extend to all groups and population that currently face barriers to full social participation (i.e. migrants, elderly people).

The cultural and creative sectors are among the most affected by the current coronavirus crisis, which forces Lisette to refocus. For the upcoming years, she will be concentrating on the implementation of the “Access Maker” project due to its huge indirect impact scaling potential. Her objective is also to further intensify working relationship with city of Cologne as a key ally in creating a blueprint of inclusive political structures that can be shared with others.

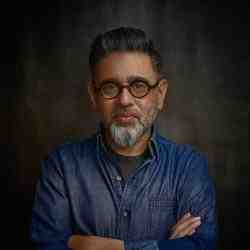

The Person

Lisette was born with an oxygen deficiency resulting in an underdevelopment of her right half of the body. Although she was lucky and had very committed parents supporting her medically and at home, she experienced bullying and unfair treatment in her early childhood. She understood that equality and fair treatment for all was not something that always naturally existed but that had to be fought for.

From very early on in school days, she was socially very active fighting for the rights of the weaker and spent quite some time on student demonstrations to bring about change in the unjust education system. Meanwhile, she always actively participated and engaged with her father in establishing one of the first theatre festival for people with disabilities, which gave her natural touch points with disabilities from early on. With the aspiration to become professionally trained in the field, she started her studies in special needs education. However, she quickly captured the rigidity of the education system as being one of the biggest barriers to inclusive education, with no room for creativity and experimentation.

Prior to founding Un-Label, she developed and implemented international and cultural projects for a media pedagogy organization working all over Europe where she understood the missing link in society: Intercultural competences, which she understands as the ability to understand, communicate with, and effectively interact with people of varied backgrounds and experiences.

She started her first project with the aim to help individuals accept and adapt this mindset, knowledge base and skill set to leverage the unique experiences, ideas and perspectives that is essential for true inclusion. With growing success in her projects and her realization about how enriching true inclusion can be when thought through right from the beginning and implemented well, she understood that her calling went beyond being an example in the field and working actively towards supporting others to do the same. Her energy today lies in bringing the right people together through networks and providing practical support in order to set free the potential she sees in a country like Germany where all people could and should live in equality, but don’t yet.