Introduction

Francesco envisions a world where every child in every city is safe and has the right to play. To do this, he has built a globally scaled model which gives children autonomy and puts them at the center of governance decisions as cities rapidly develop.

The New Idea

Francesco envisions a world where every child in every city is safe, autonomous, and has the right to access outside areas for play. To achieve such a goal, Francesco has created a process through which children get the opportunity to take legitimate action in their cities’ local government decisions, creating cities that are child-friendly and accessible. Driven by the degradation of cities and surrounding environments due to rapid urbanization and perpetuated by policy making that isn’t inclusive of youth, Francesco has set about creating a paradigm shift which puts children’s contribution at the center of legislative consultations and governance decisions.

Listening to children and seriously considering what they have to say is rarely a hallmark of inter-personal relationships, nor common societal organizations, especially when it comes to governance issues. Leveraging his years of experience working with youth and promoting their voices to decision makers, Francesco is demonstrating the unshakeable impact that this has on community development, building sensitivities and also the competencies of city administrators and decision makers. Francesco is showing that enabling children to have agency and a say in their city’s development is a model that makes everyone’s life better, anywhere. Francesco’s Children’s Council model and innovations which he open sources through networks, provides the pathways for cities all over the world to start building cities for children, with children.

Almost 30 years after starting The City of Children in the small city of Fano, Italy, there are now over 200 cities globally who are part of this network, granting children an active role in local governance. Through a unique model that helps children build skills such as leadership capabilities and teamwork and practice empathy, children go through a process of seeing their communities as belonging to not just themselves but also to the natural environment, the elderly, other citizens, and many others. As such, children go through a process of allowing cities to transform where they can regain urban spaces – spaces that provide enjoyment and help develop kinship and friendship – something which they all need as much as adults do.

Asking local administrators, especially mayors, to consider the child rather than the adult as a parameter of city government means trying to stop the degenerative processes which affect urban livability. It means adopting a different and progressive view of administrative policy decisions; for example, moving away from management that favors cars to management that favors pedestrians allows the city to be re-developed from multiple points of view. To be effective, this process must be based on citizens active involvement, where children of the city become real agents of change. Their involvement and active participation in this process is not limited to traffic patterns; it can affect urban development in many unique ways.

Francesco believes that the re-appropriation of the urban environment, the recovery of various forms of play, and autonomous movement in cities is essential for the healthy development of the child and above all for the development of the city itself. Francesco as such built the City of Children to be a replicable, universal model that should be in every city in the world.

The Problem

Since the end of World War II, decisions made in Western countries have largely taken the path towards rapid urbanization. Today, urbanization is a global phenomenon which encapsulates around 4.2 billion people globally, with the speed of growth only accelerating and predicted to be 2.5 billion more by 2050 (UN World Urbanization Prospects). These rapid changes bring with it unprecedented pressures and challenges, not only to the city itself but also to its inhabitants, especially children and youth. Challenges such as increased pollution are increasingly common in many parts of the world. It is thus not surprising to see the direct consequences of this urbanization, in the form of increased use of automobiles and children resorting to spending more time indoors. Other common consequences of this urbanization include traffic congestion, sedentary lifestyles, depletion of green spaces, increased air and noise pollution and a growing dent in social cohesion.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) states that all children have the right to play. According to studies on cognitive development, it is during the very early days, months, and years of life that a child’s development is most important. In fact, before a child enters a classroom for the first time to start their schooling journey, the foundations for their personality will be almost set. A big variable for this foundation is the cognitive and social processes that a child experiences, often best developed through the simple act of playing. The outdoor environment is an important arena for promoting healthy child development; spending time in outside spaces is positively linked to a range of physical and psychological outcomes. Independent mobility is identified as an important contributor to children’s social health, by giving them opportunities to build and sustain their bonds with peers and develop their relationship with their neighborhood and local community. Through their independent movement in the neighborhood, children develop social cohesion and contribute to community social wellbeing. Children’s interactions with people other than peers are central to their notions of community and through their use of outdoor spaces they become visible and can nurture their sense of security and belonging.

For children to fully enjoy the experience of playing as well as developing the cognitive benefits of doing so requires a few basic conditions to be met, namely, the ability and space to explore and to socialize with others without being accompanied constantly, all within safe environments. Today’s urban cities do not give all children this fundamental right and freedom and those who do have it are slowly seeing these opportunities disappear. While people continue to migrate to urban cities all over the world for better economic, social, and creative opportunities for themselves and their families, the cities themselves have become increasingly difficult to govern because of the complexity of social, health, cultural, and economic diversity of communities. The governance decisions taken on urban planning and development of cities will disproportionately impact youth, with 60% of all urban residents expected to be under the age of 18 by 2030 (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2003; UNICEF, 2018).

While it is not predicted that urbanization will slow down anytime soon, it becomes imperative to look at how cities can be developed in a way that fundamentally nurtures the wellbeing, growth, and development of children, particularly through the access of play in open spaces. A big reason why cities have increasingly had an impact on children’s ability to play is that children are quite often alienated from the decision-making process when it comes to local governance and also forgotten as stakeholders in the design of these cities. The forces which drive governance in many parts of the world tend to be economic, with decision makers often failing to realize the long-term implications on the very economy of not nurturing the wellbeing and freedom of children to play today. As children don’t have any say in what their cities and communities should look like, the design of the areas where they grow up, the facilities they have access to, and the people they ultimately get to connect to are determined by those who are making decisions, with little consideration for children.

The opportunity here is that children are increasingly recognized as social actors and agents of change at community level and have even been described as ‘catalysts’ in the creation and maintenance of social capital. Francesco Tonucci is leveraging the power of children and youth as decision makers to transform the cities of today into beacons of growth and safety for the children of tomorrow.

The Strategy

Francesco launched the City of Children in 1991 to build his vision of creating cities which have children as decision makers and hence enable the freedoms and needs they have to be met. These needs include being able to go out, meet friends, and play safely within public spaces, without the need for guardians. Fundamental experiences such as exploring, discovering, being surprised, being bold and overcoming obstacles and risks from time to time all contribute to the development of a healthy adult personality. These experiences help children make appropriate behavioral choices in response to different situations and allow a better understanding and development of perception. Important throughout this process is the development of vital defensive life-skills, skills which, when under constant supervision, are vastly restricted. Children do not consider a place as their own unless they have been able to freely experience it.

In order to drive this vision, Francesco has built a model based on three main pillars: children co-designing and participating in planning, children’s right to play, and the development of children’s autonomy. The first leverage point that Francesco uses is to identify and understand how local government meetings/consultations work. These meetings, which are common in most parts of the world, quite often discuss new developments, major infrastructure projects and other issues pertaining to the local region. Francesco identifies these bodies of governance as being the best entry point to get the voices of children to be heard and their meaningful input. Deep community engagement is the only way to ensure that the voices of vulnerable populations are considered in the city building process. This is especially important for citizens below the legal voting age who have a limited means of shaping of the world around them.

Targeting children between the ages of 6-12, Francesco developed the concept of a Children’s City Council, compromised of youth from the local region or city they are a part of. Typically tying up with all the local schools in the region and having representation from all major private and public education facilities, the youth on the council number around 30 young people. The local council often provides a facilitator to support the structure of the monthly meetings, but the agenda, issues at hand, and other rules for the council typically get set by the youth themselves. The topics that are spoken about during these consultations range from the opening up of new playgrounds, children’s safety, access to public transportation and so on. By design the Children’s Council is an extension of the local municipal corporations and set up in a way where the children’s council regularly meets local governance leaders to present their ideas and demands that are of collective importance to them. As the children represent their schools, they carry the concerns and voices of the other youth whom they study with and live around. This entire process empowers the children of the city as they see it as their own city for the first time and offers a window of opportunity for the local council to direct budgets or make policy changes based on the demands of the youth. For example, the Italian city of Fano has increased its cycle paths by 40% thanks to the Children City council proposals. The Spanish city of Pontevedra has extended the 20 miles per hour speed limit to the whole city.

Francesco provides a mechanism for children to exercise their changemaking potential by sharing ideas about and proposing solutions to the problems they see around them. Children’s voices are heard by adults who become more open to and respectful of their input, creating a paradigm shift in terms of how they see children’s roles in society. Children are not just individuals who need to be nurtured and taken care of, they are actual problem solvers. This shift in mindset is being seen across continents where Francesco’s model has scaled. Decisions are not made for children; they are made by and alongside them.

Francesco realizes that to put children at the core of local governance, there needs to be action beyond just representational acceptance. Francesco believes that this does not work in isolation. To this, Francesco has created a community certification model that allows local businesses, schools, and other stakeholders to become certified ‘Children Friends’, where they are recognized for taking action to promote for youth friendly cities as well as being safe havens for children to go to when they need support when they are hurt, lost, or in danger. This certification program has now expanded into one of City of Children’s most successful innovations, to make cities and suburbs safer and easier for children to be pedestrians in, particularly from school to home. The school to home program which creates safe pathways for children in close by localities to walk together in groups from home to school and creates new roles for community members (businesses, houses, schools etc.) to be ambassadors of this idea and be safe havens for children when needed. By creating new actors in this system and shifting the dynamics to include children in decision making and the community as changemakers, the vision becomes one that is shared among all and thus concrete changes are created by all. Across all the 200 cities that have implemented this program, there have been no incidences of harm to any children while they have been walking to school and, on average, the percentage of children walking to school increased from 10% to 60%. By also making schools partners in this program, Francesco has seen an increased demand for enrollment in these schools as they are seen by parents as more ‘aspirational.’

Francesco’s model over the last 30 years has successfully been replicated in over 200 cities across the world, including countries such as Italy, Spain, France, Switzerland, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Lebanon, and Turkey. His model has touched the hearts and minds of thousands of key stakeholders, including families, schools, politicians, businesses and so forth. Many of the cities that have replicated the model successfully have seen a number of progressive changes in their cities development, favorable to children. Furthermore, his programs have impacted the work and strategy of many other organizations such as UNICEF, which launched a big investment in its ‘City Child Friendly’ program, with a view of making urban cities more children friendly with the help of children. A Spanish association called ApFraTo (Associòn Pedagogica FRAncesco TOnucci) was founded in Spain in 2001 by Mar Romera, University Professor in Granada with the aim to spread Francesco’s ideas. By using his voice to amplify the idea across platforms, through his writing, and with old and new networks, Francesco is engineering the possibility of making every city in the world child friendly, with many others coming on board and becoming champions of the idea.

Leaders now see how including children in their work is a leverage point that puts issues on the table that otherwise wouldn’t be heard. Hermes Binner, mayor of Rosario, Argentina (third most populous city in the country) from 1995 to 2003 used to declare he learned how politics should work thanks to The City of Children. He eventually became the Governor of Santa Fe and ran for Argentina’s presidential election in 2011 coming second with 17% of votes. He championed Francesco’s model until his death and wrote the introduction to one of Francesco’s books.

To further the scale of his work, Francesco and his team have created completely open source toolkits and concrete modules with over 10 hours of content for anyone to access. The toolkits and content bring together best practices in setting up Children’s Councils, case studies from different cities, management of risks, and many other informative inputs that empowers anyone to set up this model. In fact, Francesco’s model has been scaled not just to local governance bodies in other cities but also implemented by headmasters, mayors and any other stakeholders who want to create an organization that brings in youth input. The impact has meant not just safer, more open, and livable cities for children but also better schools, access to more resources, a better environment, and other benefits as well. The COVID-19 pandemic and countries’ lockdowns have been an opportunity for Francesco to spread his ideas and methodology through the web. New educational needs were raised, and the Argentinian Minister of Education asked for his advice to re-open schools. He held webinars with more than 10,000 participants and he is now working with his team on web solutions to ensure his model can be replicated at a faster pace

Francesco’s work has had long-term impact on the young people involved in his work. A survey taken in 2018 of 100 adults in their late twenties and early thirties, who used to be in Children City Councils from 1992 to 1999, has shown how that experience has influenced their perception of citizens' rights and duties. Most participants see themselves as needing to be active players in civic engagement, especially towards issues pertaining to children, and opening up their right to play. Furthermore, adults who participated in the survey after being part of the council as children have shown to have increased problem-solving skills. Police reports in main cities where the program has been held for more than 10 years have shown a significant decrease in car accidents and no deaths related to cars and traffic.

Independent studies have also been carried out to measure the impact on autonomy for children who have participated in the home-school walking program. Groups of children across several geographies and contexts between the ages of 8-11 were investigated, all using different methodologies to get to school (some by car, others walking as a part of the program, others accompanied by an adult etc.) The tasks included a sketch map of the route and drawing the route on a blank map of the neighborhood. In order to investigate the role of autonomy in the development of a full understanding of the environment in which they live, the children were asked to use landmarks to find their way around and mark on a blank map the position of significant components of their environment. The children's freedom of movement in the neighborhood was investigated by indirect observation. The data was then analyzed and discussed as a function of the children's method of mobility, their age, and gender. Children engaged in Francesco’s program who were going to school on their own achieved the best performances in both making a sketch map of the itinerary and in drawing their movements on a blank map. Even when the representation of the environment in which they live is taken into account, the key role played by autonomy is confirmed.

Francesco has published more than 10 books translated in four languages about child development and his pedagogy theories, which continue to be a reference point for making cities more children friendly.

The Person

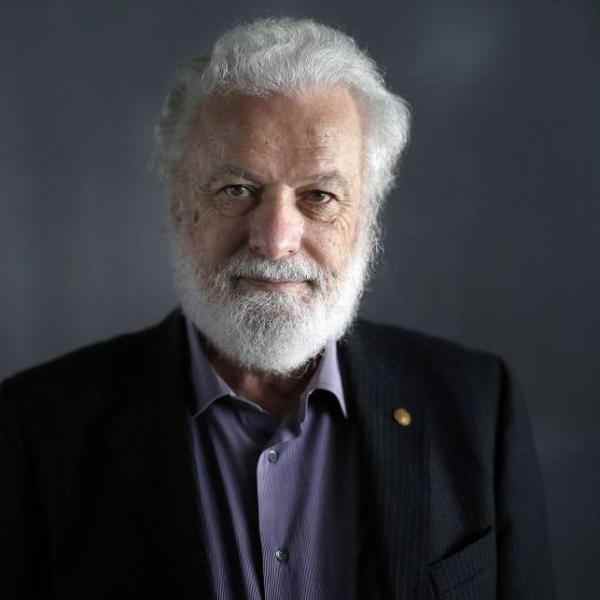

Francesco Tonucci was born in Fano, Central Italy in 1941 during World War II. One of his first memories as a child that he recalls was when his city was bombarded by the Allies, littering the sky like fireworks.

Francesco grew up in a low-income family, where his primary playmates were his three other brothers. Because they used to live in a very small apartment, his memories of the best places to play were not in the hallways of his house or a specific room but always outside on the streets or the countryside with open areas. His elementary and middle school years were defined by a struggle for academic growth and he often received poor grades. While Francesco wasn’t the best student, he excelled in creative arts, especially drawing. He grew up frustrated that no one valued or noticed his talent in drawing. This is when he started to realize that the way schools are designed, and teaching is delivered is not inclusive for all children. Furthermore, he realized that children hardly have a say in design of policies that ultimately define what they are taught, the cities they live in, and other facets that impact their lives. Francesco’s fortunes turned during his high school years, where he graduated as the top student from the region and gained a scholarship to join a University in Northern Italy, not because of any major structural changes but more because of sheer determination to do well.

Francesco was engaged with a Catholic Youth movement while he grew up, where he used to lead group discussions, challenging his friends, and opening up safe spaces to speak about issues that youth faced. This is when he started to build his leadership skills, sharing responsibilities with his mates, and helping to facilitate discussions that contributed to their own personal growth. His civic participation continued during his university years, where he was an activist promoting access to education for children from low-income families. Coming from a belief that the current education system would leave weaker children behind, he actively tried to connect with many pedagogists and other stakeholders to show the need for change. He went on to subsequently study Pedagogical Studies on his own from the Catholic University of Milan after which he kicked off his professional career as a primary teacher.

His teaching career carried on demonstrating his creative prowess that he showed as a school and university student, where Francesco launched a new model in the classroom to help children creatively develop themselves. His efforts were recognized by his peers after they resulted in better learning outcomes. Naturally, Francesco was then invited to the Italian National Research Council and in 1966 he became a researcher at the Psychology Institute of the CNR (Italian National Research Council).

Throughout his career, Francesco has contributed significantly to various facets of child development including its connection with schools, a child’s family, and their environment. In May 1991, Francesco helped the town council of Fano to organize a week dedicated to children, one which would change the city forever and leave a lasting legacy. Children and experts took part in conferences, exhibitions, and meetings, all revolving around a common point: the idea of making children and their development the focal point of policies. On the last day of the week, a Sunday, the streets were closed to traffic so the children could play and make the open spaces of the city their own. Inspired by the success of this week and the impact it had on the children and the community, Francesco set about dedicating the rest of his life building The City of Children, an organization that would drive the idea of children having a right of autonomy and a say in the governance of their cities all across the world.

Since 1968, Francesco has also become a household cartoonist working under the pseudonym Frato. Using characters with funny characteristics as tools to spread important messages to young people, Francesco has seen this creative medium as a powerful anecdote of the direction the education system needs to move towards in bringing the best out of students.