Introduction

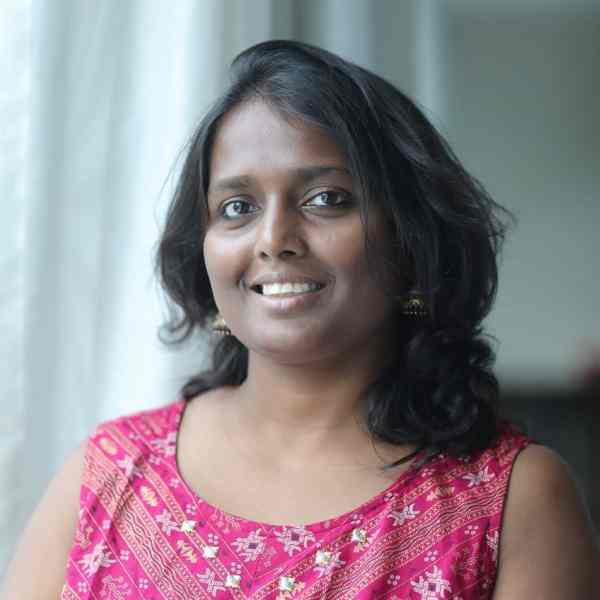

Deepa Pawar is building a movement to create leadership among NT-DNT communities, especially among youth and women, to exercise mental, health and livelihood justice in Maharashtra.

The New Idea

Deepa Pawar founded Anubhuti in Badlapur, India in 2016 to end the health, cultural and livelihood injustice endemic to India's marginalized Nomadic and Denotified Tribes (NT-DNT). She does this through building a large network of proximate and frontline NT-DNT leaders, especially women and youth, action research and documentation, protecting and promoting cultural heritage and identity, and bringing mental, sexual and reproductive health justice.

Deepa Pawar founded Anubhuti in Thane District, Maharashtra, India in 2016 to end the health, cultural and livelihood injustice endemic to India’s marginalized Nomadic and Denotified Tribes (NT-DNT). She does this through building a large network of proximate and frontline NT-DNT leaders, especially women and youth, action research and documentation, protecting and promoting cultural heritage and identity, and bringing mental, sexual and reproductive health justice.

Emerging as a Ghisadi, an Indian nomadic blacksmith community, leader at 16, Deepa was early to identify three major generational blocks among the NT-DNTs (Nomadic Tribes and Denotified Tribes, approximately 10% of India’s 1.4 bn population). First, a long social, economic and cultural repression of these historically marginalized and landless communities has led to the failure of their access to constitutional rights, resulting in poor public assertion. Second, the communities’ gross absence of "mental health justice" as well as sexual and reproductive rights, particularly for women and youth. Lastly, their Indigenous cultural knowledge is misrepresented by others, underrepresented, or absent in the knowledge commons. She began her work with Maharashtra, a state that is home to 10% of India’s NT-DNT population.

By clearly recognizing the historical and intersectional barriers shaped by her own lived experiences, Deepa has successfully activated 700 proximate NT-DNT youth and women leaders, who are, in turn, widening a leadership network. As the community’s trusted members, they are often quick to detect threats and risks to the community’s constitutional, mental, sexual and reproductive health rights.

To unite dispersed NT-DNT communities, Deepa uses traditional and new art forms, music, and cultural practices as tools of shared identity and solidarity, and in doing so, Anubhuti activities help build confidence among their communities. In existing and new gatherings, art and music are used to teach about mental, sexual and reproductive health and justice so that all understand complex topics. Women and youth leaders often lead this practice-based education and mobilization that directly speaks to different demographics—young adolescent girls and other women about body dignity, men about assisting women in their families during periods of menstruation and pregnancy, and those with partners about contraceptives for men, sexual and reproductive health. In communities with very little know-how about mental, sexual, and reproductive rights, Deepa and other leaders take the help of art, music, and even traditional games to provide education and ways to access rights.

Deepa is also creating new cultural research, documentation, and publication methodologies to end the existing post-colonial and oppressive practices. Her well-recognized mixed methods approach, unique in India and globally, is led entirely by marginalized youth and women and incorporates tools such as audits, participant observation, and in-depth interviews. Over eight years, Anubhuti and its community leaders have researched and documented many at-risk languages, dialects, art, music, and cultural practices. As a result, the NT-DNTs are reclaiming community-based research and documentation while leading a healing and repairing process after suffering for a long from cultural data extraction, misappropriation and commodification—all without remuneration and informed consent.

Lastly, Deepa is building pathways for mental, health and sexual reproductive health justice for the NT-DNTs. She believes that mental health is a social justice issue, particularly for these marginalized groups. By pinpointing the root causes of mental illness, distress or imbalance, and the resulting discrimination or violence to a marginalized social identity (of gender, caste, class and sexuality), Anubhuti’s community leaders are building new healing and repair processes with a justice approach.

The Problem

Despite 10% of India’s 1.4 billion population belongs to the NT-DNTs, there is a sheer lack of cultural or administrative knowledge about these communities. On the contrary, they have long been dehumanized by being termed as "criminals-by-birth", starting as the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 during the British Raj, and later as "habitual offenders" by the Indian law enforcement even after the Act’s abrogation in 1952. This has led to the NT-DNTs’ systemic socio-economic marginalization through segregation, targeted criminalization and harassment, and denial of jobs. They have been forcibly made landless and deprived of financial and, eventually, social and educational access. Many are nomadic, struggling to mitigate disaster, sexual, reproductive and mental health risks. Their art, culture and Indigenous knowledge are disappearing fast and are otherwise extracted by people outside of these communities without any recognition or remuneration.

The NT-DNT’s lack of or limited access to constitutional rights, public benefits, education, healthcare and even basic amenities or any identification documents, owing to their landless status, makes them highly vulnerable. Of the 140 million NT-DNT population, only 2% or less are represented in academic, legal, and research fields. This glaring disparity has led to a massive gap in public awareness of leadership roles within these communities. Frequently subjected to severe violence and discrimination, they often internalize their criminalization to cope, thereby accepting and normalizing the injustices inflicted upon them. In Maharashtra’s Thane district, many NT-DNTs live in tents because the state does not recognize them as residents with access to basic amenities. They are also evicted by state machinery to find alternate lands for their tents as new constructions begin. There is minimal effort to treat them equally and with dignity as fellow humans by integrating them into mainstream society through education and livelihood opportunities.

Many NT-DNT communities’ traditional art, history, and cultural practices, be they songs, music, or languages, are dying due to various factors. Historically, most of India’s service providers and entertainers whose services have been reduced to begging in modern times, street performers, and semi-nomadic traditional art and music practitioners belong to NT-DNTs. One factor is the lack of documentation in general and in public systems. Most of these practices are passed on through oral narratives or die away with time. Often, they face persecution from the police and authorities for performing in public places and so many are forced to leave these practices. They are also pressurized to speak the dominant language instead of their native language to hide their identities. This further adds to their state of vulnerability.

There is a massive lack of documentation and research on the lives of the NT-DNT communities in India. The lack of access to education and academic endeavors prevents them from documenting their struggles or day-to-day lives. Those who have some access to school education also drop out without completing their secondary education, as they are forced to migrate, and most of them are a shifting population. There are no proper systems to support children from this community to access formal education and girls are married off before the age of 17 years due to high social insecurity faced by their parents. Documents that are available about these communities are mostly written by outsiders, and their points of view often portray them in a degrading light. The NT-DNT’s cultural heritage faces significant risks due to outsiders who engage in extractivist and post-colonial research practices. These practices often involve extracting data from the community for their own benefit, frequently leading to anonymizing or misrepresenting the NT-DNT’s contributions. The lack of proper documentation and recognition leads to the erosion of their cultural identity and livelihood opportunities.

The NT-DNT’s precarious legal, social, and economic status has an alarming impact on the sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) of women and trans people. Women do not have access to either information or access to medical treatment despite rampant menstrual, sexual and reproductive health issues. Discrimination against them, exacerbated by criminalization, and issues arising from their nomadic lifestyle add to SRHR crises. These problems multiply in emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or natural disasters. Access to food, shelter, health care, safety in the workplace, education, mental health, and overall social security are rendered worse than usual. For example, cases of mob lynching and abuse of women are often reported upon NT-DNT women’s attempts to enter a village for toilet use or for matters as basic as trying to sell their wares.

The Strategy

Deepa is building a large network of Nomadic and Denotified Tribes (NT-DNT) leaders to help their communities attain sexual and reproductive health and mental justice and stop cultural identity erasure. To do this, she uses a four-pronged strategy. First, she activates proximate and frontline NT-DNT youth and women leadership through a specialized selection and using an in-house training and curriculum. Second, she uses art, music, cultural practices and gatherings as tools of shared identity to organize, affirm self-identity and train health and constitutional rights. Third, together with these leaders, she devises community and evidence-based action research and outreach methodologies to document, publish, protect and promote at-risk NT-DNT cultural heritage. Fourth and lastly, she is building pathways for holistic health-justice and dignity for the NT-DNT communities.

The word “Anubhuti” is inspired from the Buddhist philosophy that means to experience and to empathize, and these values form the core of Anubhuti, Deepa’s organization. Deepa and her team identify potential NT-DNT community leaders through long-term collaborations, using a process called “No-criteria Selection” (NCS) which challenges hierarchical 'merit' based selection processes. This process recognizes each community’s context and, within that, each leader’s context and applies to all Anubhuti’s leadership identification initiatives, including its flagship Guts Fellowship for emerging young leaders. Also, all such leaders further use this process to mobilize their communities’ leadership. Within the NT-DNT communities, specific areas are identified through needs assessments. Over time, potential leaders emerge from the youth and women who regularly participate in their activities, recognized for their skills, passion, and commitment to progressive values. Many of them who are otherwise excluded in jobs or socially are provided mentorship to emerge as community leaders. Anubhuti also ensures maximum representation of the most vulnerable within each vulnerable group in its selection process, resulting in nurturing more women and trans leaders. Almost 95% of women of Anubhuti’s leaders are single, widowed, or pregnant, have mental or physical illnesses, do not possess the necessary government IDs, are domestic violence victims, and many are from other such intersectional vulnerability groups including transwomen.

Deepa’s first strategy is identifying and activating NT-DNT grassroots youth and women community leaders. Noted NT-DNT, Dalit and Bahujan civil liberties and rights advocates have helped select more than 700 leaders, a significant majority being women and transpersons, who Anubhuti has trained and nurtured. For the training, Anubhuti uses the vocabulary, curriculum and methodology it has developed based on a two decade-long community-based action-research, initiatives and results. The training helps the leaders understand the systemic barriers to justice for themselves and their communities and create a nuanced plan to ensure the most vulnerable members can attain social justice. These leaders have built, together with their communities, plans with an understanding of the community’s strengths, needs, and barriers using Anubhuti’s frameworks. They are also peers to each other, complementing each other in organizing and mobilizing their community members. The community leaders Anubhuti has activated have helped 25,000 women reclaim their social safety roles to attain health, livelihoods and cultural justice in the last three years. Though NT-DNT women and youth remain Anubhuti’s focus, it also engages men in tent communities. Despite being exposed to a patriarchal environment with a relatively more basic amenity access, men participate and organize children’s safety, women’s SRHR and mental justice training initiatives, supplementing the women and youth leadership.

Using the same leadership-building process, Anubhuti’s Guts Fellowship has prepared over 50 next-generation young professionals by going beyond conventional skill-building. It teaches them the professional soft skills required in different sectors, including legal and research knowledge, so that many NT-DNT youth can be eligible for jobs. Guts Fellows are often from tent and forest-dwelling communities and are also survivors of disasters, violence, and other extreme crises. All the leaders, including the Guts Fellows, also participate and organize larger cultural and sports events. In 2020, when public authorities imposed strict lockdown at the onset of COVID-19, Anubhuti mobilized NT-DNT activists and grassroots organizations in 15 Maharashtra districts to alert the authorities of the health emergency NT-DNTs faced. Maharashtra’s Minister of State and other policymakers responded in some time, met with NT-DNT leaders, and asked state authorities to act immediately. This collaborative initiative resulted in two local courts and two district collectors acting swiftly, resulting in administrative surveys of NT-DNT’s health crises, which were long overdue, and addressing immediate health crises.

In her second strategy, Deepa uses and revives traditional art, music and cultural practices, and uses other public gatherings as tools to engage NT-DNT groups and members within communities for a shared identity. This traditional art, performance, and musical forms are either tied to NT-DNT’s livelihoods, are dying fast, or both. By forming strong partnerships with artists and musicians, Anubhuti and its leader network have also created modern art and musical forms akin to both the community identity and Anubhuti’s focus areas. For instance, Guts Fellows, in collaboration with communities, organize cultural gatherings that include skits focused on ending child labor and drug abuse. These issues are prevalent among NT-DNTs due to external dominance, high unemployment, and various forms of exploitation they encounter. In these gatherings, community women leaders teach the prevention of sexual and reproductive health issues while playing traditional games. As a result, drug addiction was reduced by 90 % among youth, sexual and domestic abuse dropped by a staggering 95%, and school dropout rates were reduced by 80% in communities where Anubhuti intervened. Women learned for the first time that they could report to the police in case of domestic violence. Similarly, Anubhuti and its leaders perform music celebrating NT-DNT, Dalit, and Bahujan resistance and provide training on access to mental health justice through musical performances. The collective efforts and heightened visibility through these cultural activities have also led to tangible improvements in access to fundamental rights and civic amenities for the NT-DNT communities. For example, their efforts have resulted in better access to clean drinking water and electricity supply, which is inaccessible to most people in these communities. Through this, Deepa recognized the importance of acknowledging the capacity for resistance and positive action in both the community members and those in positions of authority.

Deepa founded the NT-DNT youth cultural group consisting of NT-DNT, Dalit and Adivasi members called Badlache Parv Kala Manch, which uses traditional and modern musical performances, plays, poetry, and digital literature to educate NT-DNT and other marginalized communities on rights and education. Manch has successfully performed the traditional musical forms of NT-DNTs across all Maharashtra administrative districts, such as Laavani, Bharud, Kirtan, Owi, Powada, Jatyavarchi Gaani. It also uses digital literature such as doodles, comics, memes, and Reels and modern rap music in its outreach. The Manch has created content around pertinent constitutional rights such as the Right to food, safety, dignity, information and education. This initiative has reached nearly 10,000 people through performances, resulting in more leaders being selected for Anubhuti’s leadership programs.

As a part of her third strategy, Deepa is building community- and evidence-based action research and outreach methodologies, documentation and publication to protect and promote at-risk NT-DNT cultural heritage. After researching for a decade, Deepa has detailed extractivist and post-colonial research challenges while creating alternative citizen research methodologies. These practices are documented in her published books and other notable journal, newspaper and magazine publications. By conducting empirical research together with the community, these leader-researchers identify cultural practices that are either at risk or directly provide livelihoods. While studies led by non-community members have historically anonymized or portrayed participating artists and their communities poorly, Anubhuti’s network leaders publish artists’ innovation and resistance, attribute them by publishing their names, and identify their communities. The research outcomes are shared with participating communities first and then disseminated and discussed widely to boost community morale and livelihood opportunities for practicing artists. The methodologies are edited and revised based on new learning and published to be useful for NT-DNT and other marginalized groups with repressed and erased cultural heritage.

Deepa’s first book, Gadiya Lohar, documents the iron tools and craft of her own community—the Ghisadi people. The book features Poladi Baya, documenting women’s stories based on her research in 22 Maharashtra districts. It is the first book to be written by a Ghisadi woman which captures the struggle, leadership contribution, resilience, and survival narratives of 8 women, whose stories are representative of hundreds of women like them from a feminist, anti-caste, environmental and constitutional justice lens. The book is in Marathi, Maharashtra’s official language, and are being used in university courses in Maharashtra, as well as for community-based research by other NGOs. Peer-reviewed journal articles by Deepa and other leaders highlight the direct impact of existing policies on NT-DNTs’ lives and livelihoods and socio-cultural heritage, leading to policy reform discourse. Within Anubhuti’s larger researcher network, 45 youth and women community leaders collect ground-up citizen data and record the moral, ethical and consensual data collection praxis. The impact can be seen in the reclaiming of pride in the community. When their arts and cultures are published in noted journals and other platforms, there is a historic shift in their self-perception - especially important for the youth for the courage to face the world. In a context where they only heard and saw their identities being vilified and criminalized, the community is accepting and adopting their culture plays a huge role in its preservation.

Deepa’s fourth strategy is to help community leaders identify and redress sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and mental health injustice in each community context. By considering access to health as a grave systemic justice barrier rather than merely a health issue, she has built pathways for NT-DNT leaders to identify, research and document, publish and notify authorities for redressal and attain justice for community members. She coined and developed the Mental Health Justice framework, emphasizing that mental health, particularly that of NT-DNTs, is a grossly neglected issue and a severe historical injustice. Mental Justice details the lack of access to toilets, sexual and reproductive health-related critical information, medication and products, and women’s access to menstrual hygiene know-how or products—since many NT-DNTs live in tents. Like Deepa’s other strategies, this strategy focuses on solving the root cause of an issue of those affected the most within the NT-DNTs—women, transpersons and youth. Anubhuti’s network leaders, including the Guts Fellows, identify the deep-rooted caste, gender, and other socio-political and economic discriminations that lead to mental health crises and injustice. They use the Mental Health Justice framework to build community training modules and peer training along with the affected individuals and communities for a holistic path to recovery.

Multiple major Indian donors, such as Dasra and Mariwala Health Initiative, collaborate with Deepa to take aspects of the Mental Justice framework through training courses to other organizations and practitioners pan India.

In the next ten years, Anubhuti plans to expand its reach to five districts and 125 villages. The organization aims to build a robust team of over 100 members. Additionally, Anubhuti envisions developing a second line of leadership consisting of 5,000 trained community members who will actively work in the 125 villages.

Anubhuti has learned from nature and communities that scaling solely by numbers is unsustainable. The most sustainable, organic, and ethical scaling approach is to grow deeper into the roots by reaching more diverse aspects of the NT-DNT as they gain experience. This deepening naturally leads to numerical growth, connecting them more extensively with the Bahujan majority. Anubhuti plans to collaborate with community-based organizations, schools, colleges, and Ashram Shalas (residential schools) across districts, ensuring replicability and accountability. Program participants will be trained as facilitators, leaders, and peer mentors, who will then scale the programs within their own areas. They are key community members from diverse groups (women, youth, trans, disabled community leaders) who lead their programmes. By fostering multiple lines of leadership and adopting a mentoring role, Anubhuti aims to enable scaling through community effort. For example, leaders who attend a mental health justice workshop can request similar workshops for peers in other districts, with Anubhuti supporting these requests and mentoring leaders to organize these events. To sustain and scale their efforts, they will prioritize documentation and continue to publish their work for more visibility.

Since its inception, Anubhuti has directly engaged over 150,000 NT-DNT members and more than 900,000 through indirect interventions. Nearly 3,000 of these are front-line community leaders who work together within their communities. More than 700 youth and women leaders lead Anubhuti’s major programs.

The Person

Deepa was born to her Ghisadi nomadic tribe parents, who raised her and four sisters in a Mumbai suburb. She belongs to one of the most oppressed communities in India, in that she comes from a family where her father was a person with disability who passed away, leaving her as the oldest child of a single mother at a young age. Being a young woman with younger sisters without a father from a nomadic tribe put her in a critically vulnerable situation. Despite her experiences of migration and socio-economic discrimination, her perseverance for justice-making shaped her as a leader. Her family struggled immensely to provide education and safety to the daughters. Deepa would have dropped out of school in the fifth grade if a teacher did not encourage her to continue. In her seventh grade, her family urged her to quit school and get married because of high social insecurity and extreme poverty and resourcelessness where they were unable to cope with the expenses of her schooling. She went on a hunger strike against her family to advocate for her education and to convince her family—this incident marks her first resistance towards injustice. She persuaded her family to enroll her in a school where she studied and earned money by babysitting children from her community. Deepa faced discrimination from her classmates and teachers in school due to her skin color, her torn clothes and simply because of her background. Unfortunately for Deepa and her community members, they face this daily. But Deepa harbors no bitterness towards people who wrong her and her community. She strives for a rehabilitative and restorative way of dealing with these matters, evident in her work and relationship with the Anubhuti team.

When she turned 14, she got a job at a nonprofit working on education, which employed young girls to maintain mobile community libraries, earning her 300 Indian Rupees (US$3.59) monthly. But for Deepa, who loved reading from childhood but had no access to books, this was a turning point. She got to read and distribute books to children in her community which contributed to her strong research, curriculum-building and writing ability.

In 2005, a big flood swept Mumbai, and Deepa lost her father to illness a few years later because of the infections he had picked up wading in and out of the dirty water, saving his little girls from being submerged. Deepa had to raise a family before turning 20, continue her higher studies through correspondence course, and working with NGOs to keep her family afloat. Inspired by a Feminist leader at work, she decided to focus on intersectional feminism and justice for women suffering from caste- and gender-based violence. Her collective experience through work and life deeply inspired her to build a movement for collective and holistic justice for the NT-DNT communities.

Her work with different nonprofits including an anti-caste organization in Mumbai, helped her gain experience, skills, and understanding from an organizational standpoint. While working full time jobs, in 2013-14, she set up a community center in Dombivali near Maharashtra’s Thane district. In 2016, Deepa formally registered Anubhuti as an organization in Kalyan which was later shifted to Badlapur, a city in Thane.