Introduction

Ahmed is empowering local people from disadvantaged rural and township communities to help them identify their social challenges and use basic ICT skills to develop grass-root solutions, through a model of co-creation and engagement, where people understand ICT as a platform for overall community development and not only as a skill to enhance employability.

The New Idea

Ahmed’s idea is not just another network of ICT centers in disadvantaged communities, but rather a model of engaging disadvantaged communities to ensure that local people are able to utilize basic ICT skills to develop tailor made solutions to social challenges they face in their day to day lives. The model facilitates a multi-faceted process of community engagement, mapping and profiling to help people come together and identify the social needs of the local community and co-create ICT programs that are specifically tailored to address those needs. Ahmed’s objective is to ensure that local members in disadvantages township communities are able to understand ICT as a tool which can be used to design local solutions to their local problems and not just as a medium of information dissemination and social networking. Through his organization called Siyafunda Community Technology Centers (CTC), Ahmed has developed a network of Community Knowledge Centers (CKCs) run by selected individuals from the communities themselves which serve as contact points of the engagement process. The idea is to empower individuals from the community to be able to own and manage the centers within their communities. As a start off point, all the hubs offer generic IT hardware and software skills and courses to local community members at a low cost to boost IT literacy for the community and enhance people’s employability. Ahmed’s innovation goes beyond this to transform the centers into platforms of facilitating community forums around key events designed to understand the pressing social problems they are facing as a community. Through events like youth days, career path development days, ICT outreach and awareness programs, door to door surveys and other relevant themes, Ahmed unlocks the community’s social capital and brings people together to discuss pertinent issues, understand the key challenges they face and participate in the creation of local ICT based solutions which become the basis of each center’s programs.

For example, if the community profiling, (through various forums) reveals that there is lack of entrepreneurial skills for small business owners (like local street vendors), the particular center will design a business skills program targeting the particular skills gaps to ensure that entrepreneurs in the community are developed and empowered to run their small businesses efficiently. Some programs that have come up in other communities through this engagement model are youth employability and work place readiness skills for school leavers, effective service delivery and community engagement program for local government officers (mayors and ward counsellors), facilitation of automation of prepaid services like buying electricity using mobile phones from local community distributors (spaza shops) to minimize queues. In another community, Siyafunda is running a basic business entrepreneurship program for local vendors and spaza shop owners to ensure that they run their small businesses effectively and professionally. Siyafunda’s model allows for flexibility to ensure that each CKC has different tailor made programs for its community catering for the specific social needs of that particular community and this is what distinguishes Ahmed’s model from other centers offering access to computers. The essence of the model is to ensure that people move beyond mere ICT skilling towards empowering local people to use ICT as an enabling factor for community development.

Ahmed is working with about 80 community partners, corporates and funding organizations in 7 provinces of South Africa reaching out to townships and rural communities through 65 CKCs. Ahmed has created a franchise for Siyafunda CKCs through which he has been able to scale out the model to all 9 provinces in South Africa through a network of about 80 partners. Each CKC congregates an average of 5 community development forum meetings a month where more than 200 people are able to meet and discuss social issues that affect them.

The Problem

Most disadvantaged communities and townships in South Africa are challenged with ICT illiteracy and lack meaningful ICT skills that are relevant to improve the living standards of people in the community. Although people are getting more and more exposed to IT gadgets like mobile phones, in most communities these are used merely to facilitate the dissemination of information mostly through the social media and not necessarily to enable people to acquire skills for individual as well as community development. Despite increased ICT exposure in South Africa, the ICT literacy level for township and rural communities is still very low as compared to middle class societies in urban areas (Survey of ICT and education in Africa: South Africa country report). A number of colleges and institutions provide ICT skills to townships and some even in rural areas in the country. However, most of these institutions hand down pre-designed generic courses in computer skills through a top-down transactional method where community members are not involved in deciding what programs are in line with the social challenges faced in their community. ICT is generally perceived as a career option to enable access to information technology related jobs and not a platform of engagement for community development.

Most ICT hubs in the communities offer access to internet and other services like printing, typing and scanning. Although these services are important and help bridge the communications gap, they do not provide spaces where community members are challenged to identify their social needs beyond basic ICT literacy. With the dynamic nature of ICT, there is a constant change in the relevance of hard skills and programs that are applicable now could no longer be necessary in 5 years and could be rendered obsolete. This questions the relevance of ICT programs that focus on equipping people with hard ICT skills without helping them translate the knowledge into practical useful ways that can be applied to solve their everyday challenges in the real world. Technology experts have concluded that ICT is no longer the long celebrated answer to development unless people are empowered to adopt, adapt and translate technology to suit their environment and their needs (UNESCO, 2005)

On the other hand, there are a lot of CBOs, government departments, corporates and development organizations working to on various community development initiatives in many disadvantaged township communities and rural areas. Most of these are have networks to reach out and mobilize community members on issues of development. However, they do not have the tools and resources to provide a platform where community members are empowered to design ICT based programs and incorporate these in their community development plans. Further, most development initiatives by these organizations are brought into the communities as already designed programs and community participation is done as a mere process of selling the programs to the members. Communities are therefore usually not involved in the actual process of program design and as a result most development initiatives are viewed as foreign (brought from outside the community) with no proper buy-in from the people for sustainability.

The Strategy

Siyafunda’s model is based on simple principles of collaborate, capacitate and complement. The idea is to develop processes that that bring key community stakeholders together to collaborate and discuss social challenges in their communities and empower them to think of ICT based solutions to those problems and thereafter to enable creation of a multi-stakeholder network for implementation. The core of Siyafunda’s strategy revolves around the Community Knowledge Centers CKCs which form knowledge hubs and key points of reaching out and interacting with community members to engage them in a needs assessment process on other development issues beyond computer literacy. The hubs are managed by local community members and this brings a local perspective to the CKC and fosters ownership of the space by the community making it easy for them to engage and collaborate.

The first step for any community to access the model is for them, through key contact points (CBOs, community leaders) to express interest to Siyafunda. Siyafunda will only work with communities that understand the value of the model and who have expressed interest to have a knowledge center for community development. The community identifies a local individual who is willing and able to manage the CKC as a platform of engagement. The individual is assessed if he has the right qualities to manage a CKC to ensure that he understands the model and has commitment to community development. With his team, he is then trained by Siyafunda on the values of the CKC model including business management, entrepreneurial skills, community engagement processes and managing relationships and partnerships. Once satisfied with the management team, Siyafunda provides start-up equipment, furniture and resources to ensure that the CKC is up and running with the basic ICT courses as a start off point of community engagement. The management team then takes it from there, collaborating with key stakeholders and engaging community members through tailored events to bring on board local members in a needs assessment process. Each CKC has different programs in line with the particular community needs which may not necessarily be relevant in another community. With this bottom up process, the CKCs are accepted by the communities not only as knowledge centers but also as spaces of collaboration, networking and social interaction which strengthens social ties in the community and enhances social capital. Some examples of specific programs that came out from this engagement process are:

1) The needs assessment process in Palm Ridge community revealed that most local government service delivery protests are a result of lack of proper communication and feedback from ward councilors. Palm Ridge CKC developed a program in partnership with the local council and mobile network service providers to educate and empower ward councilors and other local government workers to be able to send mass messages to people’s mobile phones. For instance, if there is an electricity or water problem, or if the streets have a lot of potholes, community members will be informed on what the problem is and what the authorities are doing about it. The community could also instantly report faults (like bursting water pipes) and allow the council to take action before it gets out of hand to escalate into service delivery protests.

2) In another community in Germiston, the CKC has designed a program of basic business marketing for informal traders, street vendors and spaza shop owners where they are using their basic ICT skills to develop marketing tools like fliers, brochures, posters, etc.

3) In two communities around Cartonville area, the CKC is piloting a program with the Westlands development council (a government agency) for a program called Mobi-entrepreneurs where 100 young people are undergoing training to become vendors of products like electricity, airtime, lotto tickets through mobile devices to create employment and reduce long queues at service points.

4) In Davetone community (Boksburg), Siyafunda has piloted a mobile ICT program at Boksburg prison engaging ex-convicts from the community as facilitators of basic courses to inmates as part of rehabilitation and community integration program.

5) In Ulundi, the CKC there is piloting mobile ICT centers into very rural areas to ensure that people access basic ICT literacy at their doorsteps in areas which are otherwise isolated from technology.

Apart from the grassroot programs that come out of the community engagement process, Siyafunda CKCs also runs other community development ICT programs in partnership with other big corporates and funding organizations who would want to leverage on the wide network of CKCs in implementing their initiatives. The programs however have to agree with the development plans of the community and the local CKC managers have to take a leading role in the process to ensure alignment with the community’s development needs. Some of the programs offered through this collaboration are: (1) Neotel is piloting a survey of IT skills gap through 10 CKCs, thereafter to recruit 1,000 young people from the communities and train them in those particular skills and connect them to the job market as a drive to boost youth employment in IT; (2) Microsoft is using all CKCs to reach out to young people from disadvantaged communities for their ‘employability’ program which provides employment readiness skills to young job seekers; (3) A partnership with Junior Achievement South Africa where they have extended their business entrepreneurial skills program to communities through CKCs to benefit out of school youth running informal small businesses.

Through a franchise model, Siyafunda is engaging 80 communities in 7 Provinces of South Africa in about 65 CKCs: 50 in Gauteng; 2 in Free State; 5 in Mpumalanga; 1 in North West; 1 in Northern Cape; 3 in Kwa-Zulu Natal; and 3 in Limpopo running various programs tailor-made for the communities. The franchise model allows for a wide spread of the CKCs without overstretching the parent organization. The CKCs get their income from funding partners for their programs and also fees for the generic ICT courses they offer to the community, and they pay 10% administration fees to Siyafunda for certification and managing partnerships and relations. Almost 200 people graduate from each center per year with accredited ICT qualifications that enable them to access employment opportunities. However, the value of the CKCs lies beyond creating employment opportunities through access to hard ICT skills but rather, in providing a platform for the communities to come together, talk about their issues and be able to think of relevant and practical grass-root solutions together with fostered partnerships with other organizations. This is why Siyafunda measures the success of each CKC not just through the numbers but through the intrinsic changes occurring in the community through people’s exposure to ICT, for example, how rural community leaders use the mobile SMS platform to send out a call for a community development forum meetings or how local vendors are able to develop a simple excel spread sheet to be used in calculating income and expenditure of their informal businesses.

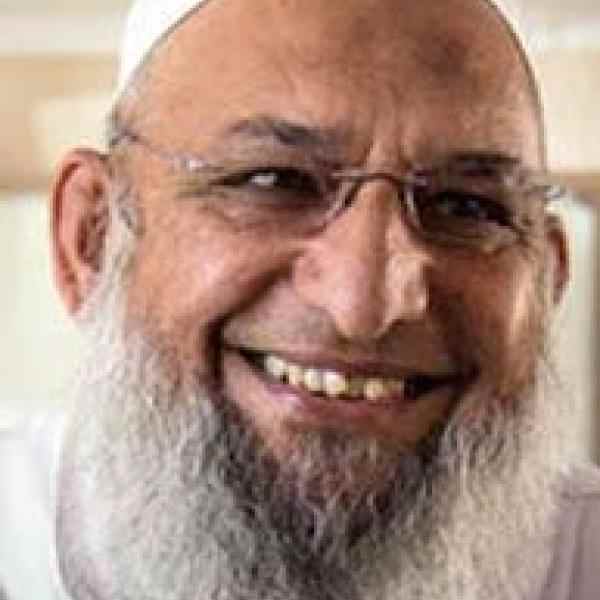

The Person

Ahmed was born and raised in Germiston in the city of Johannesburg, South Africa. Growing up in a staunch Islamic family, he was taught at a young age the values of Islam one of which was “we have been created for the benefit of human kind and we are not for ourselves”. At the early age of 16 years, he was involved in community development initiatives through the Islamic community institution in his area and this was his first contact point to community development work. In the the 70’s and 80’s, Ahmed was involved in politics as a teenager, rebelling against the apartheid government and mobilizing the community to protest against injustice. He campaigned for the position of ward councilor in his community when he was still a teenager. Although he did not win (he got 40% votes) it gave him a deeper understanding and connection to the social challenges faced by township communities. Ahmed worked for Makro (a retail chain store) for 30 years starting from a supervisory position and rising in the ranks to an executive position in the early 1990’s. He developed a passion for computers and acquainted himself with IT and handled various management positions in the IT department of the organization.

In the early 2000’s, he retired from the corporate world and decide to take time off to travel. He visited India and was impressed when he saw how much was invested in ICT infrastructure for disadvantaged townships and rural communities and learnt a lot on how important ICT literacy is in community development. This inspired him into thinking on how he can use ICT not only for computer literacy, but as a tool of community empowerment and development. He realized that it was important for local community members to be able to access affordable ICT literacy and skills at their doorstep. In 2005 he started developing partnerships around his idea (first with the local government) and in 2006 he registered Siyafunda and opened his first CKC in his community. Originally, the idea was to extend affordable ICT skills and knowledge to community members for employability, targeting the skills gap. Ahmed would do surveys around to find out which ICT skills gaps exist in the job market and come back to design packages that would offer those skills to the community and link them to the job market.

He then realized that the social challenges in the communities go beyond the mere need of ICT skills for employment, and that there is need for a more integrated and participatory intervention where ICT would be used to design community development programs targeting specific community needs. He decided to turn the ICT hub into a knowledge center and a platform to engage the community and understand their social needs. He wanted the community to be not only consumers of technology but also co-designers of community development programs that directly target the gaps in their social lives. He engaged the local government again around this idea and together they did a profiling of the community using door to door surveys and realized that people were not happy with the way the local government (ward councilors) are engaging with the community in service delivery. To address this problem, a program was designed to help local government staff to use ICT to disseminate information about community projects, meetings and use SMS as a tool for communication and to get feedback from the community around service delivery. This was the basis of the CKC model on which Siyafunda is based now. From one CKC in Germiston, Siyafunda kept growing with CKC as the entry point into each community to provide a platform for engagement and needs assessment. Siyafunda now is operating in 7 Provinces in South Africa through a franchise model that is working very well as a scaling strategy without straining the organization’s resources.