Introduction

Through a community-based crime prevention approach, James is generating new social fabric for a caring society in communities with high instances of crime. His innovative approach for trust and safety building cultivates community leadership across difference to foster the emergence of peer social services that better meet the needs of the community.

The New Idea

James uses a community-based early intervention crime prevention approach to mitigate and address instances of crime in Indigenous communities, restore the family unit, and generate new social fabric for a caring society. James’ model stewards the development of citizen- and youth-led community patrols to cultivate and empower new leaders from the community to establish trusting relationships between diverse community members. The patrols act as an entry point, where future leaders can participate, engage, and experience their own ability to act and effect change. James’ work is directly contributing to the design and development of culturally relevant Indigenous peer social services, addressing the most urgent needs of the community. Some of these services are positioned as intermediaries between community members and formal social services (law enforcement, healthcare, education), thus further advancing reconciliation efforts between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

James’ model was developed, and operates, in contexts with high instances of crime. His approach flips the emphasis from downstream law enforcement to upstream crime prevention. He does so through community patrols coordinated and led by citizens who walk the streets of their communities in an effort to proactively build solidarity, trust and safety in heavily policed communities. This approach draws from traditional Indigenous concepts of security and care taking. Community patrollers are a positive physical presence within the community; they act as a peacekeeping force for harm reduction in a non-threatening, non-violent and supportive way. James’ idea is unique because it provides an early response to criminality with the hope to reduce and avoid the need for police involvement, state interventions, or the activation of the criminal justice system, while also restoring communities’ responsibility and capacity to protect vulnerable members of society. As a result, it shifts crime reduction from a reactive, punitive law enforcement approach to a proactive, non-violent and collaborative crime prevention approach. James’ model also engages police forces in meaningful ways to change deeply held institutional mindsets, practices and norms of established law enforcement agencies so they can develop trusting relationships with community members. Police engagement occurs in a few ways: inviting police officers to participate in community-led patrols to build relationships and learn with and from community members by walking together; having the police on the board of his organization; as well as engaging members of the police force in collaborative projects, such as supporting youth to exit situations of exploitation and trafficking. James is also co-designing youth mock patrols with the police forces and incorporating them into the education system to inspire youth to become active peacekeeping leaders in their community.

James’ new idea is engaging community members to build capacity for new leadership in the community and create of a whole range of culturally relevant peer social services addressing the community’s needs and challenges. As such, James is cultivating a robust support system to empower community members to own both their problems and solutions. As of 2020, it has led to the development of a barrier-free food security program, a reduced-barrier healthcare program and initiatives to sustain the family unit before child welfare services intervene to take Indigenous children from their parents. As of February 2020, James’ model has spread to over 55 communities across Canada and he has been invited to share his approach at the UN World Urban Forum. James’ decolonial spreading strategy is rooted in the belief that healing needs to be self-initiated to allow the transformation to be completely owned by the communities, resulting in longer lasting impact.

The Problem

In 2015, the conclusion of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) laid bare the extent to which the traumatic legacy of colonization and residential schools created conditions where Indigenous people are disproportionately battling with poverty, homelessness, addiction, and various forms of violence. Discrimination and division run deep, at times leaving Indigenous women fearful of carrying out everyday tasks such as hailing a cab. Indigenous people who are most at risk of becoming involved in crime often face multiple systemic problems, including: racism, domestic violence, community violence, poor access to health care and education, inadequate housing and limited employment options. These problems generate hostility, stress and demoralization within the affected population and can lead to criminal behaviours. Indigenous people are overrepresented in the Canadian criminal justice system both as victims and people accused or convicted of crime. A 2020 report published by Canada’s Office of the Correctional Investigator shows that while Indigenous people account for roughly 5% of Canada’s total population, they represent 30% of its prison population in 2020 – an increase of 11 percentage points over the previous decade.

Typically, in Canada, crime prevention efforts defer to enforcement institutions, such as the public sector police forces that are associated with and commissioned by the three levels of government (municipal, provincial and federal). The role of these police forces is to protect law abiding citizens from criminals and punishing crime when it arises, as opposed to prevent crime and address the roots causes and risks factors that are causing criminal behaviours in the first place. Pre-colonization, the Anishinaabe people (a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples residing in what are now called Canada and the United States) provided security to their communities through clans that formed the governance structure for meeting the communities’ social, economic and political needs. The Indian Act, the residential schools system, the Child and Family Services Act and other colonizing practices and legislated policies, have effectively dismantled traditional structures, such as security and the family, within Indigenous communities. Police forces – perceived as part of the state’s colonizing apparatus - are feared, distrusted and disliked by many Indigenous communities. Police remain in reactive roles, where they are expected to punish criminality, without meaningful training or tools to understand Indigenous cultural traditions, and thus failing to create the bonds of trust needed with what are believed to be highly criminal communities. Community members often express contradictory views about police forces. Some feel there is a need for increased policing, in the hope that it will reduce crime, including street gang activity, the drug trade and sex tourism. But many also express profound fear and distrust of the police. A study in the Dufferin neighbourhood in North Winnipeg showed that for most residents, the police are an awkward presence within the community, as residents do no not trust police officers to deliver the services that the community is expecting of them.

The homicides that plague the city of Winnipeg, earned it the nickname ‘Murderpeg’. The high rates of violent crime are primarily a North End and inner-city phenomenon in Winnipeg, where most of the population is Indigenous. Violent crimes increased by 18% over the last 5 years in Winnipeg and property crimes have increased by 44% over the same period of time. Moreover, the Winnipeg Police Service receives over 6,500 missing people reports each year. The main response to the rise in crime has been an increase in policing and incarceration; while incarceration rates are going down all across Canada, this is not the case in Manitoba where 70% of the province’s prison population are Indigenous. Societal, community, relationship-based and individual risk factors for crime affecting Indigenous communities are concentrated in Winnipeg, home to the largest urban Indigenous population in Canada. There, the legacy of colonization has resulted in high levels of poverty and food insecurity within Indigenous communities. James states than in the communities that he serves, it is easier to buy a crack pipe at a corner store than it is to buy an apple. The neighbourhood also has a high rate of unemployment, and one in three community members drop out of school before grade 9, leaving huge swaths of young individuals wholly disconnected from the labour market.

In addition, in Canada, there are more Indigenous kids in foster care in 2020 than at the height of residential schools. As of 2020, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has issued seven non-compliance orders against the Federal government for discrimination against Indigenous children and families. In 2020, there are more than 10,000 kids in government care in Manitoba, the highest per-capita in Canada and about 90% of these kids are Indigenous. If in the past the police have been used to further the objectives of the government in the assimilation of Indigenous people through the apprehension of children for conscription in residential schools, it continues today in the similar role of supporting child welfare agencies. The continued separation of Indigenous children from their families and the systematic breakdown of family ties have deeply damaged the social fabric required for healthy relationships within Indigenous communities and perpetuates a colonial model where Indigenous children are taken away from their families and considered wards of the state.

Compounding these challenges, Winnipeg has, since 2014, been increasingly affected by the use of methamphetamine. The Addictions Foundation of Manitoba saw an 84% increase in meth-related deaths from 2016 to 2017, going from 19 deaths where meth was a primary or contributing factor in 2016, to 35 such deaths in 2017.

The Strategy

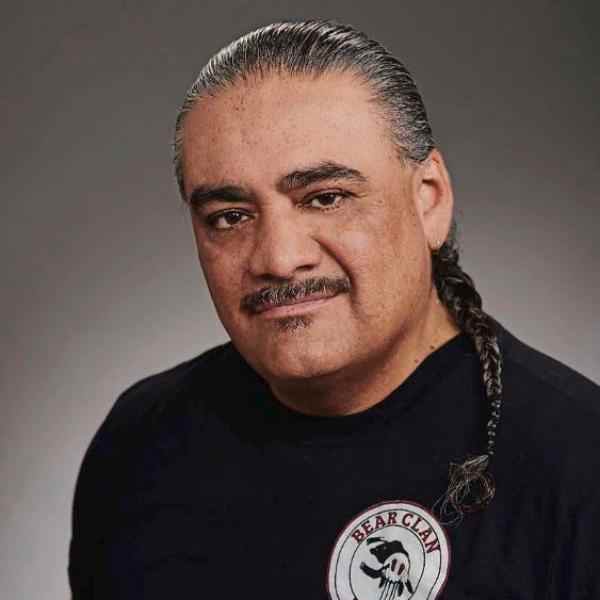

Having spent most of his life in a low-income neighbourhood of Winnipeg and member of the Peguish First Nation, James has experienced first-hand the effects of colonization and saw his community struggle with poverty, homelessness, drug addiction, sex exploitation and violence. In August 2014, a fifteen-year-old Anishinaabe girl from Winnipeg, Tina Fontaine, was found murdered after haven been lured into prostitution by people she knew. At that time, James was a truck driver and had also been working in community development for four years as chairman for the Dufferin Residents Association of Winnipeg on his spare time. Frustrated to see that there were no consequences for people involved in sex exploitation, James wanted to build a community policing program in Winnipeg to address this challenge. The death of Tina was the last straw for James, who quit his job as a truck driver in 2016 to commit full time to restoring the traditional responsibility of his community members to care for one another and build safer communities. This sense of responsibility is drawn from the Anishinaabeg clan system and governance, and specifically the Bear Clan. Pre-colonization, the Anishinaabeg nation’s governance structure saw the Bear Clan as responsible for peacekeeping and protection of the people by acting as warriors, guardians, healers and caretakers.

In 1992, Larry Morrisette tried to revive the clan structure in Winnipeg in a post-contact context: a small group of 12 Indigenous volunteers patrolled the community on the weekend, in vehicles. Despite their efforts, Larry’s model did not succeed in building trust with the community. The initiative did not take hold and eventually the initial group of volunteers disbanded after a couple of years. In 2015, James identified the need for a traditional Bear Clan structure to fill the void in his community. He then asked and was given permission by Larry Morrisette to revitalize the Bear Clan identity for community-based peacekeepers and guardians, and to use it to advance reconciliation by welcoming diverse groups of people to take on the Bear Clan identity and adopt protocols for community safety and harmony.

Initially targeting sex exploitation, James realized there was much more taking place in his community. He designed the Bear Clan Patrol (BCP) as a positive and consistent presence on the street available to families between supper and bedtime. Because he believed consistency and a strong visible presence were key to BCP’s success, James ensured that patrols, each composed of minimum five BCP members, patrolled the streets on foot (not in a vehicle) five days a week from 6pm to 9pm on weekdays and until 12am on Fridays and Saturdays in the summer; these patrolling hours correlate to the times during which criminal activity spikes in the community. The police report that crime is down in the areas the BCP is patrolling because of BCP interventions. This is mainly due because the patrollers are a strong and consistent visible presence in the community, respectful of everyone and fostering non-violent and non-threatening interactions between people.

James designed the BCP to provide an early response to situations of crisis with the hope to reduce and avoid the need for police involvement, courts and lawyers, as well as restoring in community the responsibility and capacity to protect vulnerable members. To make sure this was embodied in each patrol, James put the women – and not the men – in charge of the patrols, therefore coming back to the traditional matriarchal ways of leading of the Anishinaabeg people. By bringing the focus back on taking care of someone in distress first and building capacity to bring them the assistance they need, the BCP is bypassing the default reaction - to ignore such an individual in distress or to call the police to deal with the situation, often done without considering the devastating consequences this police intervention could have on someone’s life. James ensured that BCP members receive training on CPR, First Aid, non-violent crisis intervention, post-traumatic stress management, applied suicide intervention, dementia awareness and Naxolone administration should they encounter someone overdosing. Initially, these trainings were delivered by the Winnipeg Police Services (WPS), the Red Cross and fire-paramedics in the form of in-kind donations to cohorts of new members of the BCP. But with the growing number of volunteers involved, James has evolved this training so that experienced BCP members who received the formal training from service providers now train new volunteers. Paired with their on the ground shared experiences, these foundational trainings allow patrol members to show up in an approachable, compassionate and non-threatening way, equipped with the skills to de-escalate highly emotional situations that might happen facing someone in the middle of a drug-induced psychosis or a domestic violence crisis. These interventions interrupt the escalating sequence of events, avoiding the need to turn it into a police matter and building citizen capacity to prevent or even mitigate emergencies. By calling an ambulance instead of the police in such situations and by collecting needles on the street (145,000 in 2019) while patrolling, the BCP members effectively decrease calls for service to the police.

James knew that if he wanted to break down mistrust between police forces, service providers and the Indigenous communities to effectively work towards reconciliation, he needed to form a new relationship with law enforcement early on in the Bear Clan structure. Therefore, in 2015 James started to build relationships with the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) by inviting police officers to come walk on patrols to experience things from the way the community members see them. If at first there was hesitation from the community to bring police officers along, after spending time walking the streets together, the community realized police officers were just people like them with common needs around education, housing, food and healthcare. This important connection allows all groups to carry out their respective responsibilities more effectively to make sure the community feels safe. Through bridge building, James is actively breaking down stereotypes and misconceptions that each group holds about the other and has opened new lines of communication between the police and the community. Walking with the BCP is changing the perception police officers have of working with some community groups. The police now see the BCP as an on the ground extension of themselves because they can see and do things that the police cannot do. That is in part because it is Indigenous-led and informed, which creates trust in these heavily policed communities which have been socialized to dislike and fear the police.

On the ground, the BCP members act as the eyes and ears of the police, observing and reporting. First Nations Chiefs are now comfortable calling the police to learn about how investigations are done or to share instances of domestic violence. BCP members help with the search of missing individuals (the Winnipeg Police Services Missing People Unit receives 600 missing person reports on average each month, most of whom concern women and children) making the work of the police easier and faster to find out what happened to missing individuals. A Bear Clan missing-person’s social media post can reach over 175,000 people which extends the search capacity far beyond the police’s capacity. An additional area of cooperation with the police is when the BCP members record the license plates of individuals soliciting prostitutes and communicating this information to the police, which was started due to James’ observations of a lack of enforcement in the law of vehicle seizure after the solicitation of sex workers. Thanks to James’ and his team’s efforts to report individuals soliciting prostitutes, this type of behaviour has become less acceptable in the community.

In 2016, noticing that more and more young people were starting to use heavy drugs and that they were the most at risk of going missing or to being sexually exploited, James began taking groups of youth from the age of 10 to 17 out in the community to educate them on the hazards that were present on the street, how to protect themselves and better understand their role in the community. As of the beginning of 2020, James is partnering with the WPS and the School Boards of Winnipeg to implement their youth mock patrols program in the school system. The BCP youth mock patrol program connects schools, kids, teachers, the WPS, cadets, politicians and parents to incorporate an Indigenous cultural education component around ceremonies as well as training on personal safety, grooming techniques, and gang exit tactics. As well, there is education on how to deal with and avoid-self harm when handling a needle, recognizing the symptoms of an overdose and preventing it from becoming a lethal outcome. The program encourages cross-cultural relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth. It runs between 4.30pm and 6.30pm, the time after school when most kids are out in the street. The goal is to change their life before they get into trouble. Former gang members who have joined the BCP come to talk about their gang experience, share how they’ve changed and why they chose to work with the BCP, acting as role models for the youth and showing them that an alternative is possible. Up to 20% of the youth involved in the youth mock patrol are now preparing to become police officers. In addition, the youth mock patrols act as a direct recruitment of volunteers for the Bear Clan Patrols as most of the teenagers when they turn eighteen join the adult patrols. Bear Clan Patrols in other jurisdictions such as Calgary (Alberta), Regina (Saskatchewan) or Brandon (Manitoba), are mirroring this practice by starting their own youth mock patrols in partnership with schools and local police forces. In addition to engaging with youth, James is also working at the level of the family unit to actively divert children from being apprehended by welfare services. James’ main goal is to secure the family unity and provide early responses in situations of family crisis, such as taking the child to a safe house or to a relative instead of involving CFS.

James and his team found themselves increasingly distributing granola bars or apples while patrolling in response to ongoing requests for food from members of the community. In 2019, he decided to start a barrier-free food security program in the Winnipeg North End. James noticed that despite the number of food banks in the community, there were barriers such as a required government issued ID (which many residents in James’ community don’t have) preventing some people from benefiting from these services. The BCP food security program has no such requirements and community members can come every day if needed. James and his team also provide support to community members to access resources that are already in the community but that they might not know of – for example to get an ID or open a bank account. As of 2020, they serve 250 people on average a day, 7 days a week. James’ goal for 2020 is to establish reduced barrier and barrier free mental health and health care support for his community members. He has been traveling across Canada to educate himself about what is already being done on this matter and is working with service providers, the University of Manitoba Rady Faculty of Medicine and the Vancouver Native Health Society to design new practices to meet those who have traditionally been isolated from mainstream services. James sees this as the next step to fulfill the Bear Clan’s traditional mandate to “secure our village and bring the medicine”. As such, Bear Clan Patrols are setting a high bar for other institutions to engage with heavily policed communities.

James started the BCP in the community of Dufferin in Winnipeg’s North End in 2014 with 12 volunteers. As of 2020, the model now has 1,700 Winnipeg-based volunteers and has spread to 58 communities across Canada. In 2019, the BCP in Winnipeg counts over 45,000 hours of volunteer service. It is now garnering interest from Aboriginal communities in Australia. Non-Indigenous communities are also replicating the model such as the Immigrant and Refugees of Manitoba organization which has started their own patrol. The model is only replicated in communities that request it. James starts by checking that they have the right supports in place and by gaining an understanding of their needs. He then provides support and a start-up package for interested communities to develop their own patrol. Once the Bear Clan has been invited to patrol within a community, it becomes the responsibility of the host community to support the Patrols. This decolonial spreading strategy lies in James’ deep belief that healing has to be self-initiated in order for communities to completely own the solutions they wish to develop longer lasting impact of the initiatives developed.

The Person

James is Ojibwe, member of the Peguish First Nation. Born in Scarborough (Ontario), he has spent his entire life in Winnipeg and has experienced first-hand the effects of living in situations of poverty and violence, within a heavily policed community. James himself was convicted four times of felonies stemming from poverty-related risk factors. Despite this, he has turned his life around and the police officer who arrested him is now the Chair of the Board of the BCP. James started trucking in 2005 which allowed him to travel across Canada and observe how different communities were experiencing life from coast to coast to coast. The long lonely hours on the road helped him to draw inspiration from what he was seeing in different places to formulate a plan of action for the betterment of his own community.

James states that he has been given the opportunity and the tools to contribute to the restoration of the health and balance of his community. He has been personally affected by colonial constructs and believes that the crux of our issues stems primarily from the pushing of responsibilities while true change must first start at home. James is trying to change that and heal his community in a healthy and productive manner through bringing people together with community-based collaborations addressing the needs of the community. James is a trusted and loved leader in his community who connects with people on a deep level, seeing the human in them beyond their institutional membership. James’ end goal is to build safer communities for all while helping people understand their role in the community as a positive influence, allowing children to have a safer place to live and an opportunity to aspire to aims in life beyond gang membership. He wants to set a higher bar where we can actively build public institutions that we trust and value – not fear and hate.